Back in 1995 my wife and I visited Northern Ireland. We spent a weekend in Belfast, hardly a tourist mecca, but then again, not as bleak a city as it is often painted. Anyway its people not places that make a destination and the Irish overwhelm you with their unrelenting hospitality in both the north and the south of this enchanting country.

But for all that, Belfast was a bit different. It was incongruous for instance to hear people tell you in a broad Irish accent that they were “British to the core,” and yet that is what so many were like in Northern Ireland. Not all of course, hence the aggravation, but those who were pro-British tended to flaunt their stance. Many flew the Union Jack above their homes. Some residents painted the kerbs outside their dwellings red, white and blue; sometimes whole streets were so adorned.

And back then they had these ridiculous marches. While we were there the Apprentice Boys marched. I assumed this would be a group of young lads marching to celebrate that they were employed in a worthwhile trade. I couldn’t have been more wrong. The “boys” were well into their seventies, and were marching to celebrate some remote victory, Protestant over Catholic, that had occurred centuries ago. They teasingly marched into Catholic areas to taunt and provoke. These areas were totally devoid of Union Jacks or painted kerbs I might add. Tensions would mount and sometimes overflow into violence. It all seemed so unnecessary.

On Saturday afternoon we drove our rental car to nearby Antrim and, sitting in a park by a lake, we struck up a conversation with an Irishman who told us in no uncertain terms that he was “pro-British.” He was a bit critical of New Zealand because of our Catholic, pro-republican prime minister at the time, Jim Bolger, but he was an amusing conversationalist and we enjoyed our interlude with him. It soon became clear that his great hero was Dr. Ian Paisley. I expressed interest so he asked me if I would like to meet the reverend gentleman in person. Now I’d never had much time for Paisley, but the opportunity to meet a world figure was compelling, so I agreed that I would. Our man said all we needed to do was to go to Paisley’s church in the heart of Belfast the next morning and we could see and meet the great man in the flesh. He said he would inform the church elders that we were coming.

The church was the Free Presbyterian Church of Ireland and the service was to start at eleven. We arrived at about a quarter to eleven and were immediately conspicuous by our attire. Without exception all the women were wearing frocks and hats, and the men, suits and ties. In stark contrast Marion and I had open neck tops, casual slacks and sneakers. For all that we were made very welcome and ushered to very good seats in this large modern church.

I had expected that the area around the church would be surrounded by British army personnel and that Paisley would arrive in an armoured car; but this was not the case. Everything was calm and peaceful and there was not a soldier in sight. At the stroke of eleven Paisley strode up to the pulpit and warmly welcomed visitors to his church, particularly the couple from “Noo Zealand.”

His service, which he virtually conducted single-handedly, was apolitical, and fundamental in structure. He was a charismatic figure, and with a booming voice that needed no amplification. The sermon was edifying, the singing inspiring, and the hour passed quickly.

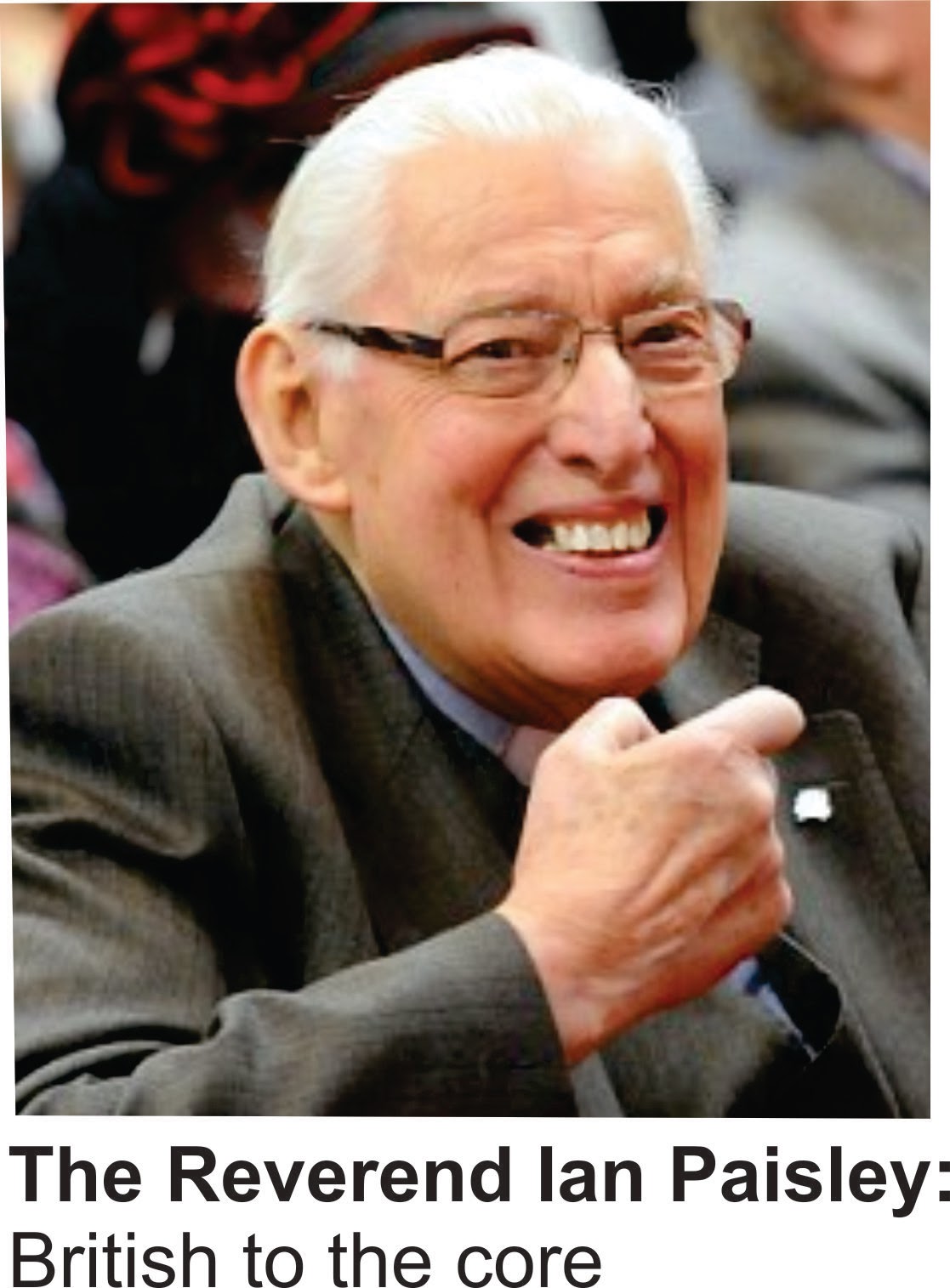

After the service I sought him out, introduced myself, and told him that I was the visitor he had welcomed. He extended his hand and with a friendly smile said, “And how’s Noo Zealand?” I had the perfect answer, “The harvest is many,” I said, “but the labourers are few.” “Same here in Ireland,” he retorted “Same here in Ireland,” and for about five minutes we chatted and laughed together; actually I laughed and he chuckled. He had a most pleasant personality.

Eventually I was led to tell him that it seemed to me that he had been misrepresented in the press. I had, in the space of an hour of corporate acquaintance and a few minutes of personal appraisal, decided this man was not the ogre the world’s media had painted him. He chuckled and said that he was used to this distortion, and that it did not unduly worry him.

Soon he was to wish us both “Godspeed” as we went on our journey and I began to wonder if Hitler, Stalin, and Pol Pot mightn’t have been bad blokes on a one to one basis too. Grossly unfair to lump Paisley with that group, but you know what I mean.

The divisive Protestant firebrand and Democratic Unionist Party leader died a couple of weeks ago; he was 88. Throughout Northern Ireland’s three decades of civil strife he was the most polarizing of politicians, his blistering oratory often blamed for fueling the bloodshed that claimed 3700 lives.

Yet in 2007, at the height of his peace-wrecking power, he stunned the world by delivering the country’s first stable unity government between its “British” Protestants and its Irish Catholics. “Dr. No” as he was widely known finally said yes and his powerful U-turn cemented a peace process that he had previously done so much to frustrate.

Paisley relished his new role as Northern Ireland’s first minister with a relaxed demeanor, most strikingly evident when working alongside his government co-leader, former IRA commander Martin McGuiness. The two men surprisingly formed a genuine, mutually respectful relationship. Joking together at events they were dubbed “The Chuckle Brothers” by a disbelieving press.

“Chuckle” is a hard word to accurately describe, but it’s the one aspect of my meeting with Paisley that remains firmly fixed in my memory.